On the morning of November 1, 1880, Denver's Chinatown lay in ruins. Every Chinese-owned business had been destroyed. Windows were smashed, doors torn from hinges, merchandise scattered in the streets. Blood stained the wooden sidewalks. And hanging from a lamppost at the corner of Sixteenth and Wazee, the body of a Chinese man swung in the autumn wind.

The night before — Halloween — a mob of 3,000 to 5,000 white men had swept through Denver's Chinese neighborhood. They called it Hop Alley, slang for the opium trade that white Denver associated with its Chinese residents. For eight hours, the mob beat, looted, and destroyed. One man was murdered. Dozens were injured. An entire community was erased in a single night.

For over a century, Denver's only acknowledgment of this atrocity was a historical marker that called it the "Chinese Riot" — as if the Chinese had rioted against themselves. The marker wasn't corrected until 2022. The dead man's killers were never punished. The community never recovered. This is the story of the massacre Denver tried to forget.

Hop Alley

Chinese immigrants began arriving in Denver in the late 1860s, drawn by railroad work and mining opportunities. By 1880, the city's Chinese population had grown to over 400 — a small but visible community concentrated in a few blocks near today's LoDo neighborhood. They called their neighborhood Hop Alley, and it was a world unto itself.

The alley had laundries — the primary occupation for Chinese men in the American West, since white businesses refused to hire them for most other work. There were restaurants, groceries, boarding houses, and yes, opium dens, which were legal at the time and patronized by white customers as often as Chinese. There was a temple, community organizations, and the beginnings of permanent settlement.

White Denver viewed Hop Alley with a mixture of fascination and disgust. Newspaper articles described it as exotic and dangerous, a mysterious Oriental underworld in the heart of the city. The Chinese were accused of taking jobs from white workers, of spreading disease, of moral corruption. The reality — that they were laborers and businessmen trying to survive in a hostile society — was harder to sensationalize.

"The Chinese of Denver are a source of constant annoyance... they are a nation of thieves."

— Rocky Mountain News, Report on the "Chinese Quarter," 1879

The Spark

The violence began with a pool game. On the afternoon of October 31, 1880, two white men entered a saloon in Hop Alley and began playing pool with a Chinese man named John Ling. An argument broke out — accounts vary as to why — and one of the white men, a laborer named Jim Turner, struck Ling. Ling fought back.

Word spread through Denver's bars and boarding houses: a Chinese man had attacked a white man. By evening, a crowd had gathered at the edge of Hop Alley. They came armed with clubs, bricks, and guns. They came drunk. They came angry about jobs they'd lost to Chinese workers, or thought they had. They came because Halloween gave them an excuse.

The crowd grew. One hundred became five hundred became a thousand. Speeches were made about the "Chinese menace" and the need to "clean out" the neighborhood. Police stood nearby and did nothing. By 8 PM, the mob numbered somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 — nearly a tenth of Denver's entire population.

Then they attacked.

The Massacre

The mob moved through Hop Alley systematically, building by building. They smashed windows and doors. They dragged Chinese residents into the street and beat them. They looted stores, taking what they wanted and destroying what they didn't. Furniture was thrown from windows. Merchandise was burned in bonfires.

Chinese residents fled in terror. Some escaped through back alleys. Some hid in cellars and attics. Some were found and beaten anyway. The violence continued for eight hours, until there was nothing left to destroy.

A man named Look Young was not so lucky. The mob found him hiding in a second-floor room above a laundry. They dragged him into the street, beat him, and hanged him from a lamppost. Some accounts say he was kicked to death before the noose went around his neck. Others say he was still alive when they hoisted him up. Either way, Look Young died that night — murdered for being Chinese on Halloween in Denver.

The Death of Look Young

Look Young, also recorded as Sing Lee in some sources, was the only confirmed fatality of the Halloween riot. He was lynched at the corner of Sixteenth and Wazee Streets. His body hung there through the night. No one was ever convicted of his murder.

The Aftermath

When dawn broke on November 1, Hop Alley was destroyed. Estimates of the damage ranged from $53,000 to over $100,000 — enormous sums in 1880, representing the life savings of hundreds of people. Every Chinese business in the neighborhood had been wrecked. Most residents had fled the city entirely.

The response from Denver's white establishment was muted. Some newspapers condemned the violence; others suggested the Chinese had brought it on themselves. Mayor Richard Sopris issued a proclamation calling for order but took no action against the mob. The police, who had watched the riot unfold without intervening, made a handful of arrests. None resulted in serious charges.

The Chinese consul in San Francisco, Frederick Bee, formally requested reparations from the federal government. The Hayes administration refused. The consul documented the riot extensively, hoping to build a case for compensation. Nothing came of it.

A grand jury was convened to investigate Look Young's murder. Several men were identified as participants in the lynching. All were acquitted. The message was clear: killing Chinese people in Denver had no consequences.

"The riot was a disgrace upon our city, but the Chinese must bear some responsibility. Their presence among us has always been a source of discord."

— Denver Tribune, Editorial, November 1880

The Erasure

Denver's Chinese community never fully recovered. Some residents returned and rebuilt, but the message had been received: they were not safe here. Over the following decades, the Chinese population dwindled. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 cut off new immigration. By the early twentieth century, Hop Alley was largely gone.

The physical neighborhood was erased by urban development. The buildings that survived the riot were eventually demolished for parking lots and new construction. By the mid-twentieth century, there was no trace of Hop Alley left in the landscape.

The historical memory was erased too. For over a century, Denver's only marker acknowledging the events of Halloween 1880 was a small plaque that called it the "Chinese Riot." The phrasing implied that Chinese residents had rioted — that they were the aggressors, not the victims. The plaque made no mention of Look Young's murder. It made no mention of the mob. It blamed the victims.

The Corrected Marker

In 2022, after years of advocacy by historians and community members, Denver finally replaced the old "Chinese Riot" marker with a new one that accurately describes the events as an "anti-Chinese riot" perpetrated by a white mob. The correction took 142 years.

The Pattern

Denver's Halloween massacre was not unique. Throughout the American West in the 1870s and 1880s, Chinese communities were attacked by white mobs. The Rock Springs massacre in Wyoming killed 28 Chinese miners in 1885. The Hells Canyon massacre in Oregon killed as many as 34. Tacoma and Seattle drove out their entire Chinese populations. Los Angeles had its own "Chinese massacre" in 1871.

The pattern was consistent: economic anxiety among white workers, racist scapegoating by politicians and newspapers, violence by mobs, acquittals by courts. The federal government refused to intervene or provide reparations. The Chinese who survived learned that American law would not protect them.

This wave of violence helped drive support for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 — the first law in American history to ban immigration based on race. The mob violence, the acquittals, and the exclusion all worked together. By the end of the nineteenth century, Chinese communities across the West had been decimated.

What Remains

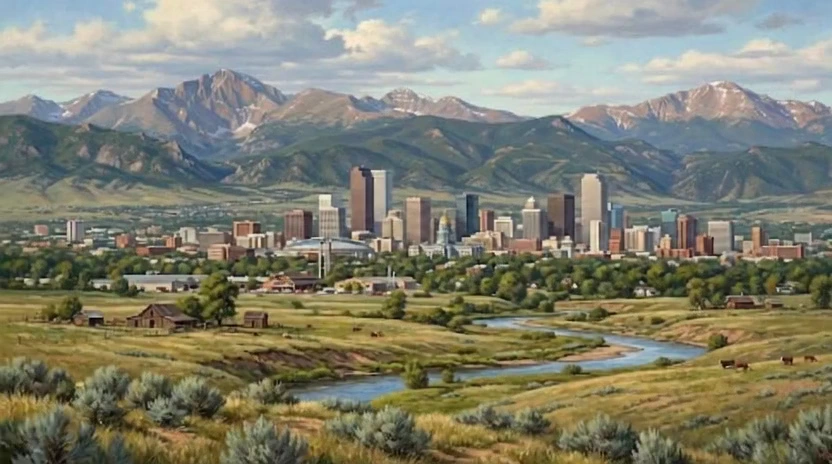

Walk through Denver's LoDo neighborhood today and you'll find no trace of Hop Alley. The buildings are gone. The streets have been renamed. The neighborhood is now home to bars, restaurants, and condominiums. Nothing suggests that 400 Chinese Americans once lived here, built businesses here, were beaten and killed here.

The new historical marker, installed in 2022, finally tells something closer to the truth. It's located at a small plaza near the site of the old Chinatown. It acknowledges that a white mob attacked the Chinese community, that Look Young was murdered, that the violence was not a "riot" by the victims but an assault against them.

It took 142 years to get that marker right. For all those years, Denver's official history blamed the victims. The city's most violent night was rewritten as the fault of those who suffered it. That's how erasure works — not just destroying buildings but destroying memory, making it seem like the victims brought it on themselves.

On Halloween night in 1880, a mob destroyed Denver's Chinatown and murdered a man named Look Young. The killers were never punished. The victims were never compensated. The city spent over a century blaming the victims for their own victimization.

Today, there's finally a marker that tells something like the truth. But a marker can't bring back the dead. It can't restore the businesses that were burned, the savings that were looted, the community that was scattered. It can't undo 142 years of official lies.

What it can do is remember. Look Young had a name. Hop Alley had a community. And what happened on Halloween 1880 wasn't a "Chinese riot." It was a massacre — and Denver should never forget it.

Finding the Site

The corrected historical marker for Denver's Chinatown is located near the intersection of 20th and Blake Streets in LoDo. The Hop Alley neighborhood was roughly bounded by Wazee, Blake, 15th, and 20th Streets. Nothing remains of the original buildings. History Colorado's online exhibit "The Rise and Fall of Denver's Chinatown" provides additional context and images.