The graves are small and uniform — concrete crosses rising a few inches from the grass, each stamped with a number. 247. 583. 891. For over a century, this was how Raleigh buried its mentally ill: anonymously, with only a hospital case number to mark where they lay. No names. No dates. No acknowledgment that a person had lived and died.

The Dorothea Dix Hospital Cemetery sits on three acres near downtown Raleigh, part of the sprawling grounds that once housed North Carolina's largest psychiatric institution. Over 900 people are buried here — patients who died between 1859 and 1970, most of them abandoned by families too ashamed to claim them. For generations, they were forgotten. Now, slowly, volunteers are giving them back their names.

The Hospital

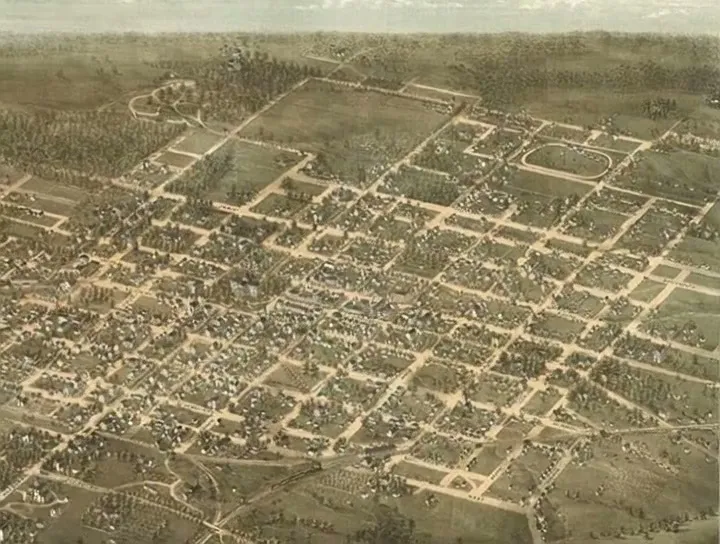

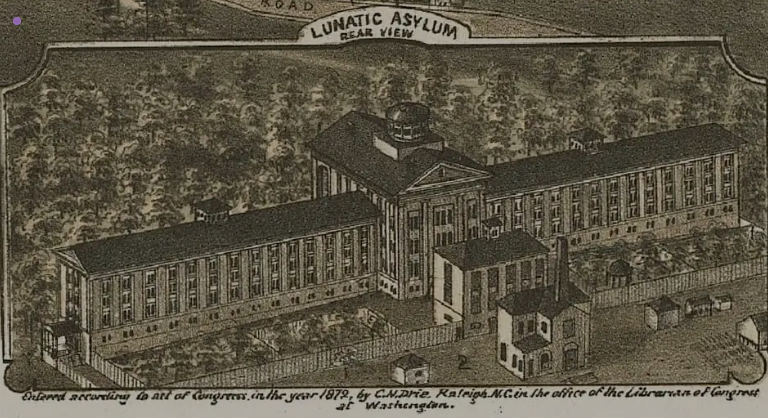

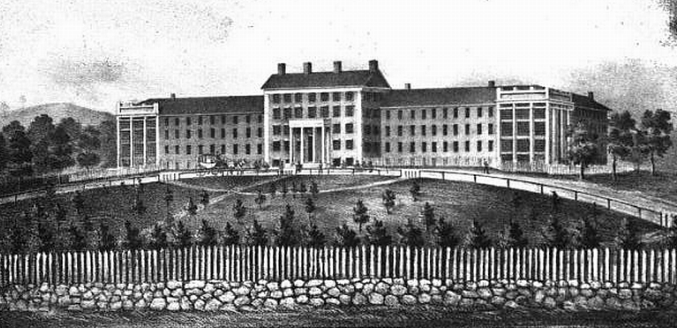

Dorothea Dix Hospital opened in 1856 as the "State Hospital for the Insane" — one of the first public psychiatric institutions in the South. It was named after Dorothea Dix herself, the reformer who fought for humane treatment of the mentally ill and lobbied the North Carolina legislature to build the facility.

The hospital grew over the decades, eventually sprawling across hundreds of acres southwest of downtown Raleigh. At its peak, it housed thousands of patients — some genuinely mentally ill, others simply poor, elderly, or inconvenient. The categories blurred. Once committed, patients often stayed for life.

When they died, most were buried on hospital grounds. The cemetery began accepting patients in 1859 and continued until 1970. The graves accumulated: rows of identical crosses, each marked with a number, spreading across the hillside like a field of anonymous memory.

"It seemed to me that a grave for that many people should be marked. It seemed a sad testament to how the mentally ill were treated back then that it was not."

— Cemetery restoration volunteer, Raleigh News & Observer interview

The Stigma

Why numbers instead of names? The answer is stigma. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mental illness was a source of profound shame. Families hid their afflicted members, denied their existence, pretended they'd never been born. Commitment to an asylum was a mark of disgrace that extended to entire families.

When patients died at Dix, their families often refused to claim the bodies. Burial in the family plot would acknowledge what they'd tried to hide — that someone they loved had been mentally ill, had been institutionalized, had died in a state hospital. Better to leave them anonymous. Better to let them disappear.

The numbered graves served this purpose. A family could tell themselves their relative had simply vanished. There was no gravestone with a name, no marker connecting them to the shameful truth. The patient became a number, and the number became nothing.

The Numbers

Most graves in the Dorothea Dix Cemetery were marked only with the patient's hospital case number. For nearly a century, not even hospital administrators kept reliable records connecting numbers to names. The patients were anonymized in life and in death.

The Forgotten

The people buried at Dix came from everywhere and nowhere. Some were genuinely psychotic — schizophrenics, manic depressives, people with conditions we now know how to treat. Others were epileptics, alcoholics, elderly dementia patients — anyone whose behavior didn't fit the norms of their time.

There are Civil War veterans in the cemetery, including Eli Hill — a Union soldier with the United States Colored Troops who had once been enslaved. There are members of the Lumbee tribe from southeastern North Carolina. There are immigrants, farmers, factory workers — a cross-section of North Carolina buried beneath numbered crosses.

Some were institutionalized for being "immoral" — a catch-all category that included everything from adultery to homosexuality to simply being a woman who didn't obey her husband. The hospital was a dumping ground for people society didn't want, and the cemetery was where they ended up when society was done with them.

The Neglect

After burials stopped in 1970, the cemetery fell into neglect. The grounds were poorly maintained. Markers sank into the earth, became overgrown, disappeared. An adjacent landfill encroached on the cemetery's edges — some graves may have been covered entirely. The dead, already forgotten, became even more invisible.

By the 1990s, the cemetery was in crisis. Erosion had destabilized the hillside. Markers were toppling. Records connecting numbers to names were scattered across multiple archives or simply lost. Nobody knew exactly who was buried there or exactly how many graves existed.

Then volunteers stepped in. Hospital administrators, local historians, and community members began a painstaking restoration. They tracked down records. They cross-referenced patient files with burial logs. They identified 750 patients buried in the cemetery and installed new markers with their actual names.

"Every time we find a name, we're giving someone back their identity. For a hundred years, they were just numbers. Now they're people again."

— Cemetery restoration volunteer, Oral history interview

The Restoration

The restoration effort has been slow and painstaking. Volunteers have spent thousands of hours digging through archives, comparing records, and physically cleaning and repairing the cemetery. Each name recovered is a small victory against a century of forgetting.

In 1991, volunteers installed a memorial wall listing the names of identified patients. Over the years, additional research has identified more — the current count exceeds 800 named individuals. But dozens of graves remain anonymous, their occupants still known only by numbers.

The City of Raleigh now maintains the cemetery and has committed to a full restoration. Volunteers continue to work on straightening markers, clearing vegetation, and researching identities. The goal is to ensure that everyone buried at Dix is eventually known by name.

Ongoing Restoration

Volunteers regularly organize cleanup days at the Dorothea Dix Cemetery. Work includes re-leveling sunken markers, clearing overgrowth, and documenting grave locations. The City of Raleigh's Parks department coordinates restoration efforts.

The Park

The Dorothea Dix Hospital campus is now Dorothea Dix Park — a 308-acre urban park that will eventually become one of the largest in the Southeast. The hospital buildings have been demolished. The grounds are being transformed into meadows, forests, and recreational areas.

The cemetery will remain. Park planners have committed to preserving and commemorating the burial ground, integrating it into the larger park as a place of memory and reflection. The goal is to ensure that even as the hospital disappears, the people who lived and died there are not forgotten.

It's a complicated legacy. The hospital did genuine good — providing care to people who had nowhere else to go. It also did genuine harm — warehousing the inconvenient, enabling families to abandon their own. The cemetery holds both truths: people who were cared for and people who were discarded, all buried under the same numbered crosses.

Walk through the Dorothea Dix Cemetery today and you'll see rows of small crosses, some with names now restored, others still bearing only numbers. Each marker represents a person — someone's child, someone's parent, someone who lived and suffered and died in a psychiatric hospital over a century ago.

They were buried anonymously because their families were ashamed. They stayed anonymous because nobody cared enough to remember. Now, slowly, they're getting their names back. It doesn't undo the abandonment. It doesn't erase the stigma. But it acknowledges that they existed — that they were more than numbers, more than case files, more than the illness that put them here.

The restoration continues. There are still graves to identify, still names to recover, still people waiting to be remembered. In Raleigh, the work of undoing a century of forgetting is measured one marker at a time.

Visiting the Cemetery

The Dorothea Dix Cemetery is located within Dorothea Dix Park, accessible from Umstead Drive in Raleigh. The cemetery is open to the public. Visitors are asked to treat the grounds with respect. Information about volunteer opportunities is available through the City of Raleigh Parks department.