Invented Before It Existed

A planned capital, a headless namesake, and the quiet ambition of the City of Oaks

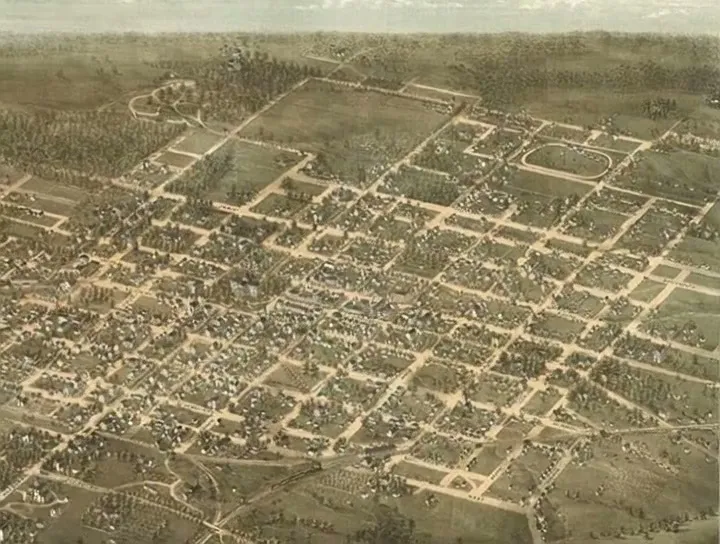

Raleigh is the only major American city that was literally invented before it existed. In 1788, the North Carolina General Assembly decided their capital should be more central than the coast, so they designated a spot in the wilderness—no existing town, no settlement, just a decision on paper that this empty stretch of Wake County would become the seat of government. They named it after Sir Walter Raleigh, an Elizabethan courtier who never set foot in America but had the distinction of being beheaded by King James I, his preserved head kept by his wife as a keepsake for twenty-nine years. A fitting patron for a city built from pure abstraction.

The weather here is Southern but measured—humid summers, mild winters, the kind of climate that forgives architectural ambitions and allows trees to grow enormous. The oaks that give the city its nickname are everywhere, canopies arching over streets in neighborhoods where the houses were built when the population was a fraction of its current half-million. Rain comes in afternoon thunderstorms in summer, in steady gray systems in winter, and the city absorbs it all into its red clay soil and its creeks running toward the Neuse River.

The historic neighborhoods developed in concentric rings from the Capitol, each wave of construction leaving its architectural signature. Oakwood, just northeast of downtown, contains one of the largest intact collections of Victorian homes in the South—houses with wraparound porches and gingerbread trim, built when Raleigh was a small state capital with more ambition than industry. Five Points followed, bungalows and Craftsman cottages from the streetcar era. Cameron Park and Hayes Barton came next, their larger lots and Tudor Revival homes signaling the arrival of the automobile and the professional class.

Research Triangle Park changed everything. Opened in 1959 on seven thousand acres of pine forest between Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, RTP was another invented place—a deliberate creation designed to keep educated North Carolinians from fleeing to Northern cities. IBM arrived, then Burroughs Wellcome, then hundreds more. The tech corridor that runs from Raleigh west to Durham and north to RTP now employs over 300,000 people. The farmland between the three cities filled in with office parks and subdivisions and shopping centers, creating a continuous metro area of two million people who identify as being from "the Triangle" rather than any single city.

Downtown Raleigh spent decades in the doldrums that afflicted every American downtown—the department stores closing, the professionals fleeing to suburban office parks, the streets emptying after five o'clock. The turnaround began in the 2000s, accelerated in the 2010s, and became unmistakable by the 2020s. New apartment towers went up, restaurants and bars filled the ground floors, tech companies moved their offices back from RTP to Warehouse District buildings with exposed brick and floor-to-ceiling windows.

The food scene evolved from Southern staples to something more varied, more ambitious. Ashley Christensen's restaurants—Poole's Diner, Death & Taxes, Beasley's Chicken + Honey—became nationally recognized, proving that a mid-sized Southern city could produce cuisine worth traveling for. Coffee roasters proliferated. Breweries multiplied. The café culture that developed downtown and in the surrounding neighborhoods would have been unrecognizable to anyone who'd known Raleigh before the boom, when the options were chain restaurants and meat-and-threes and the occasional Greek diner.

The State Capitol still anchors Union Square, the Greek Revival structure completed in 1840 after the original burned, its copper-topped dome visible from blocks away. The building feels small for a state capital, intimate in a way that the monumental statehouses of Texas or Pennsylvania could never match. Ghosts are said to walk its halls—the elevator runs by itself, books fly from shelves in the library, footsteps echo in empty corridors at night. The security guards have stories. Everyone who works there has stories. The building carries its history in ways that feel less like folklore and more like fact.

The City Discovers Itself

The Southern pace persists despite the tech money, the transplants, the accelerating change. Front porches still matter here. Neighbors still wave. The politeness is genuine, not performed, though it coexists with the same tensions that run through every Southern city—the Confederate monuments that stood for a century before removal, the historically Black neighborhoods that gentrification is transforming, the public schools that remain deeply segregated by income if not by law.

The University Town Within the City

NC State sprawls across 2,100 acres on the edge of downtown, a land-grant university that started teaching agriculture and mechanics in 1889 and now enrolls 36,000 students in everything from textile engineering to nuclear physics. The campus bleeds into the city at Hillsborough Street, a strip of college bars and cheap restaurants that has resisted gentrification longer than anywhere else in central Raleigh. Game days turn the campus and its surroundings into a sea of red, 57,000 people filling Carter-Finley Stadium, the tailgates stretching for acres in the surrounding parking lots.

The traffic tells the growth story better than any census data. Roads built for a regional hub now carry metro-area volumes. The Beltline that was supposed to encircle the city now runs through its middle, surrounded by development that leapfrogged past it decades ago. I-40 clogs daily from Cary to downtown. The sprawl continues in every direction—Apex and Holly Springs to the southwest, Wake Forest and Rolesville to the north, Clayton and Garner to the south—suburbs becoming cities in their own right, their populations tripling in a generation.

Roads built for a regional hub now carry metro-area volumes. The Beltline that was supposed to encircle the city now runs through its middle.

Fayetteville Street was pedestrianized in the 1970s, a well-meaning mistake that drained the downtown of life for decades. Now it's open to cars again, lined with restaurants and bars, alive on weekend nights with crowds spilling from breweries and music venues. The farmers' market on Saturdays brings thousands to the State Fairgrounds, the vendors selling produce and meat and baked goods from farms scattered across the Piedmont. The First Friday art walks fill the galleries. The city has discovered its own potential for urban life, and the discovery still carries the energy of novelty.

The oaks remain, though they're disappearing. Each new development takes down trees that were saplings when the Civil War ended, replacing them with landscaping that will never approach the same scale. The character of Raleigh—its canopy, its shade, its green softness—depends on trees that can't be replanted in a generation. The city that was invented from nothing continues to reinvent itself, growing faster than its infrastructure, more expensive than its longtime residents can afford, more connected to the national economy than to the state it governs. The headless courtier watches over it all, his name attached to a place he never imagined, his story mostly forgotten by the people who live here now.