Beyond the Grid

SLC’s real soul isn’t found on the tourist drags; it’s hidden in basement speakeasies, abandoned theaters, and the secret corners of the mountains that the brochures forget.

These aren't in the guidebooks. A pyramid offering modern mummification, underground tunnels beneath Temple Square, secret viewpoints with better views than the tourist spots, hidden swimming holes, and obscure museums locals guard fiercely. This is where Salt Lake gets weird.

1

Summum Pyramid - Modern Mummification & 'Nectar Publications'

In a quiet Salt Lake City neighborhood, a 40-foot bronze-and-concrete pyramid rises with the unassuming confidence of a landmark in Giza. This isn't ancient Egypt; it's Summum, a religious philosophy that practices modern mummification. Founded in 1975 by Claude "Corky" Nowell (who, upon his death in 2008, became the first to be mummified in his own pyramid), Summum offers "transference" services for both humans and pets. For around $67,000, you too can have your body preserved for eternity in a gold-covered bronze sarcophagus. Over 1,500 people are on the waiting list; 600 pets have already made the journey. The pyramid itself is legally zoned as a "winery" because Utah wouldn't approve a pyramid-shaped church—they produce "nectar publications" (ceremonial wine). Tours are free, deeply surreal, and available by appointment. Just be sure to ask about the mummified cats.

2

Price Museum of Speed

Hidden in an unassuming downtown building is one of the most significant private racing collections in America—and it's open to the public exactly three hours per month. The Mormon Meteor III is the crown jewel: Ab Jenkins drove this streamlined beast to 24-hour speed records on the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1940, averaging 161 mph for an entire day and night. The collection includes over 30 racing machines spanning a century—a 1904 Peerless Green Dragon, a 1929 Bugatti Type 35B, Indianapolis veterans, Grand Prix legends. John Price spent decades quietly assembling cars that tell the history of human obsession with going faster. No crowds, no gift shop, no velvet ropes—just you, the cars, and sometimes Price himself explaining why a particular engine note still haunts him.

3

Pioneer Memorial Museum Oddities

The Daughters of Utah Pioneers run this 38-room museum that officially celebrates Mormon pioneer heritage—but wander past the quilts and wagon wheels and you'll find one of America's strangest accidental collections. Bottles filled with human teeth extracted during the trek west. Victorian mourning jewelry woven from the hair of the dead. A taxidermied two-headed lamb born on a frontier farm. A petrified potato carried across the plains as a good luck charm. Rattlesnake rattles, dozens of them, collected from the snakes that made desert nights dangerous. A hand-carved wooden leg that walked someone to Zion. A bloodstone that pioneers believed could stop hemorrhaging. The museum doesn't play up the weirdness—it's all presented with the same earnest reverence as the spinning wheels and butter churns. That's what makes it perfect: you have to hunt for the bizarre, and it's everywhere.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

4

Neff's Canyon

While tourists and Instagram hikers clog Mill Creek Canyon every weekend, locals slip away to Neff's Canyon—a brutal, beautiful 7-mile climb that gains 3,562 feet and rewards with the kind of solitude Salt Lake's popular trails forgot decades ago. The trailhead hides at the end of a residential street in Millcreek, unmarked enough that most people drive right past. The canyon is shaded and creek-fed in summer, golden with aspens in fall, and snowshoe-worthy in winter. Wildflowers carpet the meadow halfway up. The ridge at the top offers panoramic views into Big Cottonwood Canyon that feel earned, not given. Neff's is where Salt Lakers go when they remember why they moved here—and where they don't tell newcomers about.

5

Wall Lake

Everyone knows Crystal Lake in the Uintas—it's the first lake past the trailhead, and on summer weekends it's a zoo. But keep walking another mile and the crowds vanish. Wall Lake sits in a cirque of granite, its water an impossible shade of icy green, with cliffs at the southeastern end tall enough to jump from if you're brave and stupid in equal measure. The lake is deep, cold even in August, and ringed by wildflowers that somehow survive at 10,000 feet. Locals treat Wall Lake like a secret handshake—mentioning it to the right people signals you know the real Wasatch. Arrive at dawn on a Tuesday and you might have the whole thing to yourself. Show up on a Saturday and you'll share it with every other local who reads articles like this one.

6

Allen Park (Hobbitville)

For decades, Salt Lake children whispered about "Hobbitville"—a mysterious property along Emigration Creek where tiny houses dotted the woods, peacocks roamed free, and strange hermits supposedly lived in seclusion. Parents warned kids away. Teenagers snuck in anyway. The truth was weirder than the legends: in the 1930s, a wealthy couple built a bird sanctuary here, then opened it to artists and eccentrics who constructed whimsical cabins among the trees. By the 1960s it was a counterculture commune. By the 1980s it was abandoned, overgrown, and perfect for urban mythology. In 2020, Salt Lake finally acquired the 8-acre property and opened it to the public. The peacocks are gone, but the tiny houses remain—hobbit-sized structures slowly being reclaimed by the forest, monuments to a Salt Lake that existed before conformity became the brand.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

7

Salt Lake Public Library Rooftop Garden

Moshe Safdie designed Salt Lake's main library to be climbed—a curved glass-and-concrete building with a public walkway that spirals to the roof. Most visitors never make it past the books. Their loss. The rooftop garden offers 360-degree views of downtown, the Wasatch Range, and the Great Salt Lake, plus reading nooks, native plants, and a working bee farm that produces honey sold in the gift shop. At sunset, the mountains turn pink and the city glows amber and you remember that Salt Lake, for all its contradictions, occupies one of the most dramatic settings in North America. All of this is free, open during library hours, and almost entirely ignored by tourists who came for Temple Square and left without looking up.

8

Church Office Building Observation Deck

The LDS Church's 28-story administrative headquarters dominates Temple Square—and on the top floor, open to anyone who asks, is one of the best free views in the American West. The observation deck offers floor-to-ceiling windows facing every direction: Temple Square directly below, the Wasatch Range to the east, the Great Salt Lake shimmering to the northwest, and downtown Salt Lake spreading south. Most tourists spend hours at Temple Square without ever knowing they can ride an elevator to the top of the adjacent tower. There's a small exhibit about church history, but the real draw is the view. Free, air-conditioned, and somehow always uncrowded. You don't have to be Mormon. You just have to know it exists.

9

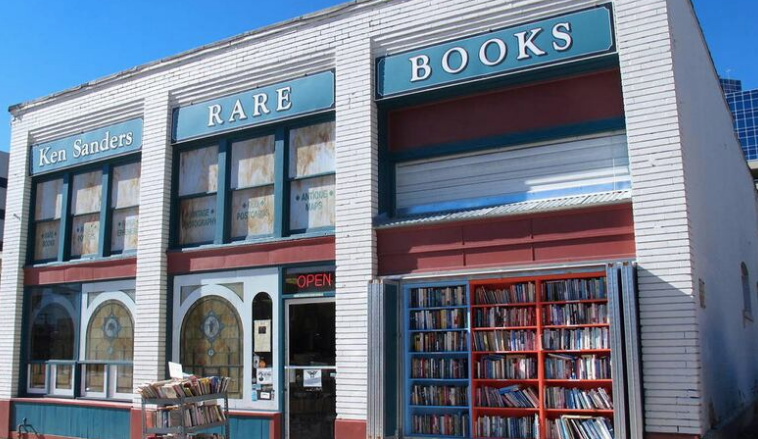

Ken Sanders Rare Books

Ken Sanders was Edward Abbey’s close friend and literary executor, which explains why this shop feels more like a desert anarchist’s headquarters than a bookstore. Crammed into a space where the aisles are barely shoulder-width and the stacks reach for the heavens, it is a defiant monument to "Old Salt Lake." Sanders specializes in the rare, the radical, and the Western—Americana, Mormon history, and the kind of Colorado River exploration maps that predate statehood. Sanders himself is often holding court, telling stories of Abbey and the desert that developers are currently erasing. It is a place for serious collectors and those who believe that a city is only as good as its archives.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

10

International Peace Gardens

Two miles from Temple Square, in a working-class neighborhood that tourists never visit, 28 countries have built gardens along the Jordan River. The Japanese garden is the showpiece—bamboo groves, stone lanterns, koi ponds, a moon bridge arcing over water lilies—but Greece, Germany, India, and two dozen other nations have staked their claims in this 11-acre oasis. Salt Lake's immigrant communities built these gardens starting in 1939, a Depression-era project that somehow survived and grew. The result is a world tour in a single afternoon: manicured European formalism giving way to tropical plantings, Buddhist sculpture neighbors Scandinavian modernism. Most Salt Lakers don't know this place exists. Even the ones who do rarely visit. On a weekday morning, you might have an entire country to yourself.

11

Kilby Court

Since 1999, Kilby Court has operated out of a space no bigger than a two-car garage in an industrial alley west of downtown—and somehow became the most important music venue in Salt Lake history. The Killers played here before anyone knew their name. Modest Mouse, Band of Horses, The Shins—all passed through this room that holds maybe 200 people if everyone breathes in. The walls are covered in band stickers and handwritten set lists. The sound is imperfect in the way that makes live music feel alive. Kilby is all-ages and alcohol-free, which means the crowd comes for the music, period. Artists play for almost nothing because the room has a reputation that travels. In a city where venues come and go, Kilby has survived 25 years on pure DIY stubbornness. Check the calendar. Buy a ticket. Stand three feet from someone who might be famous in two years.

Stay curious

New stories and hidden gems delivered to your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Explore More

Discover more curated guides and local favorites.

Salt Lake City's Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Salt Lake City's Best Restaurants

From fine dining to hidden gems and local favorites

Explore

Salt Lake City's Best Coffee Shops

Local roasters, cozy cafes, and third wave spots

Explore

Salt Lake City's Dark History

Unsolved mysteries and darker chapters

Explore

Salt Lake City's Curiosities

Fascinating facts and surprising stories

Explore

Salt Lake City's Lost Salt Lake City

Beloved places we miss

Explore

Colorado Springs Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Colorado Springs Best Restaurants

From fine dining to hidden gems and local favorites

Explore

Know something we missed? Have a correction?

We'd love to hear from you