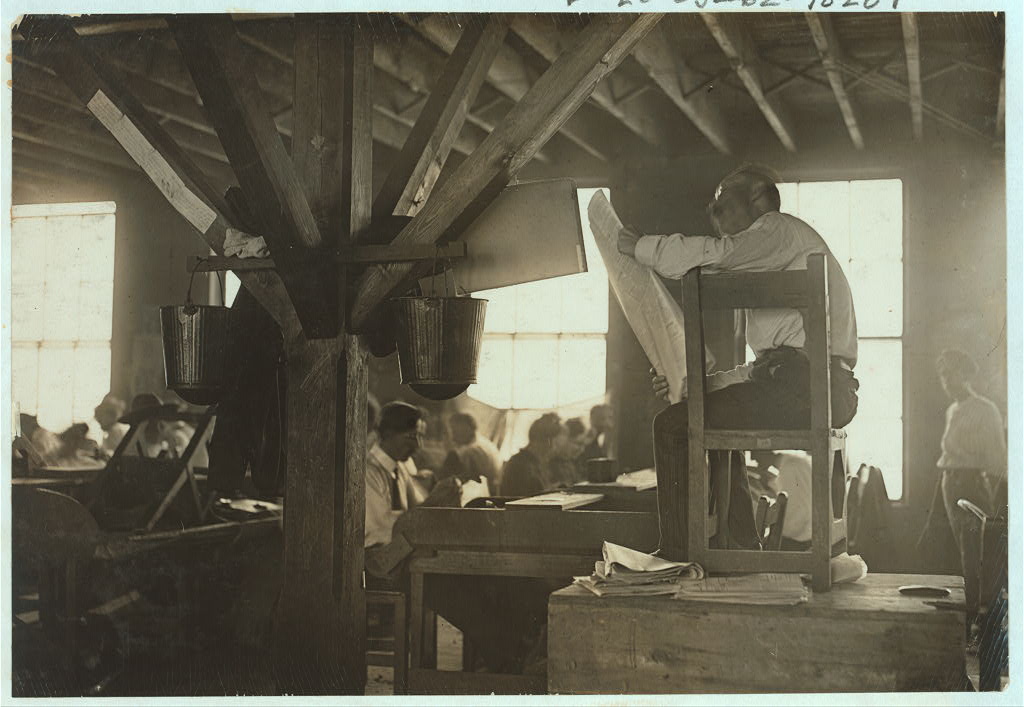

The factory floor was silent except for one voice. Three hundred workers sat at wooden benches, hands moving in precise rhythms — stripping stems, pressing leaves, rolling tobacco into perfect cylinders. They did not speak. They did not need to. Above them, on a raised wooden platform called "la tribuna," a man in a suit sat reading aloud from a Spanish-language newspaper. His voice carried across the room, rising and falling with the news from Havana, from Madrid, from the labor halls of New York.

This was a cigar factory in Ybor City, Tampa, sometime around 1910. The man on the platform was a "lector" — a professional reader, hired by the workers themselves to read to them for eight hours a day while they rolled cigars. He was reading that morning's edition of a radical labor newspaper. Later, he would read chapters from a Victor Hugo novel. Later still, he might read a manifesto by José Martí, the Cuban revolutionary who had walked these same factory floors two decades earlier, raising money and recruits for the war that would free Cuba from Spain.

The lectores were not entertainers. They were educators, agitators, and — in the eyes of factory owners — dangerous subversives. They made Tampa's cigar workers the most politically informed laborers in America. They helped launch a revolution. And by 1931, they were gone forever, killed by radio and the factory owners who hated what they represented.

The Craft

To understand the lectores, you first have to understand what cigar-making was. This was not a factory job in the modern sense — no machines, no assembly lines, no interchangeable workers. Hand-rolling a premium cigar required years of training. A skilled "tabaquero" could roll over 200 cigars a day, each one identical, each one perfect. The work was repetitive but demanded concentration. Your hands were busy. Your eyes were focused. But your mind was free.

The practice of reading aloud in cigar factories began in Cuba in the 1860s. A poet and revolutionary named Saturnino Martínez started the tradition at the El Fígaro factory in Havana. The idea spread quickly. Workers discovered that listening to novels and newspapers made the hours pass faster and transformed the factory floor into something like a university. They voted to hire readers and paid for them out of their own wages — typically contributing 25 cents per week per worker.

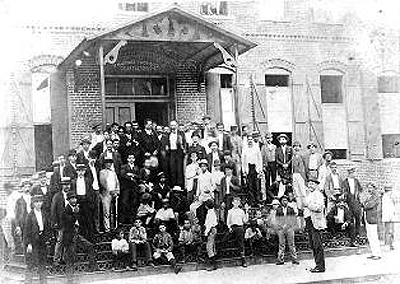

When Cuban cigar manufacturers began relocating to Tampa in the 1880s — fleeing Spanish colonial taxes and labor unrest — they brought the tradition with them. By 1900, nearly every cigar factory in Ybor City employed a lector. At the industry's peak, Tampa had over 200 cigar factories and perhaps 12,000 cigar workers. The lectores were their teachers.

"The lector was selected by the workers themselves. They would vote on who to hire, what to pay him, and what he should read. The factory owner had no say in the matter."

— Gary Mormino, Historian, University of South Florida

The Reading List

The lector's day was carefully structured. Mornings typically began with newspapers — the Tampa Tribune, Spanish-language papers from Havana and New York, and radical labor publications like the anarchist "El Esclavo" (The Slave). Workers wanted to know what was happening in the world, especially in Cuba, where many still had family.

Afternoons were for literature. The lectores read novels — often in serialized installments, a chapter or two per day. Victor Hugo was a perennial favorite. "Les Misérables" was read so many times in Tampa's factories that workers could recite passages from memory. They also loved Émile Zola, whose novels about working-class life resonated deeply. Alexandre Dumas. Cervantes. Tolstoy. The great works of European literature, read aloud in Spanish to Cuban, Italian, and Spanish immigrants rolling tobacco in Florida.

Some lectors became celebrities. The best could read for eight hours straight without losing their voice or their audience's attention. They mastered accents, changed their tone for different characters, brought drama to newspaper accounts of labor strikes in Pittsburgh or political upheavals in Madrid. Workers followed their favorite lectors from factory to factory. A great lector could command wages higher than the cigar rollers themselves.

The Curriculum

Popular works read in Tampa's cigar factories included "Les Misérables" by Victor Hugo, "The Count of Monte Cristo" by Alexandre Dumas, "Germinal" by Émile Zola, "Don Quixote" by Cervantes, and the political writings of José Martí. Workers also heard daily newspapers, labor publications, and anarchist pamphlets.

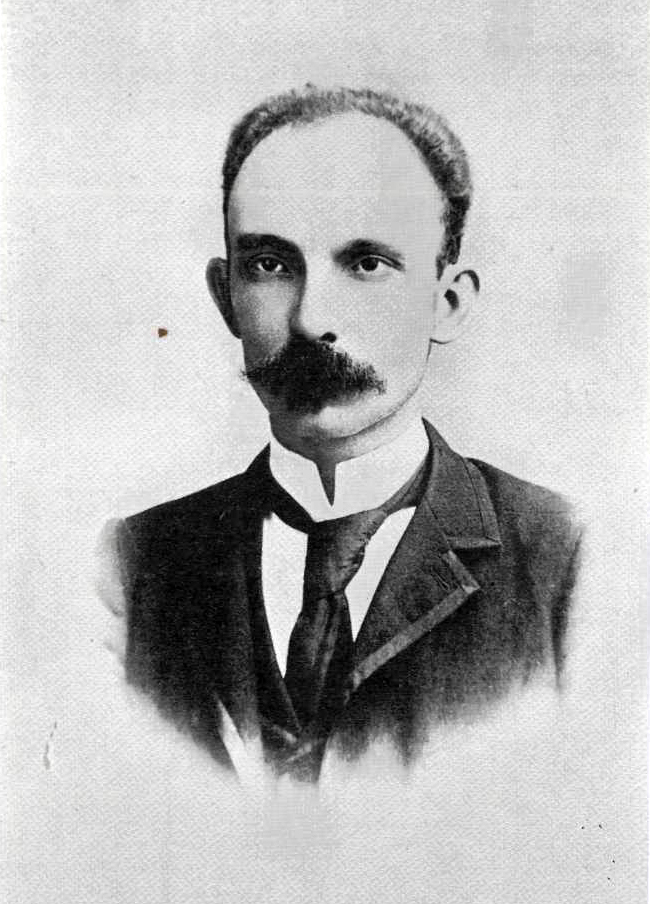

The Revolutionary

Martí was already famous as a poet and essayist, but he had a larger purpose. He wanted to liberate Cuba from Spanish colonial rule, and he understood that the cigar workers of Tampa — educated by decades of lectores, radicalized by anarchist newspapers, connected by family to the island — were his natural allies. He didn't just need their money. He needed their souls.

That night, Martí gave a speech that workers remembered for the rest of their lives. He spoke of Cuban independence, of dignity, of a free republic where workers would be respected. When he finished, the cigar makers of Ybor City pledged their support. They would donate a portion of their wages — "el día de los obreros," one day's pay per week — to fund the revolution. Over the next four years, Tampa's cigar workers contributed tens of thousands of dollars to Cuban independence.

Martí returned to Tampa repeatedly. The lectores read his essays aloud to workers who couldn't read themselves. His words echoed through the factories, turned into a kind of revolutionary scripture. When the Cuban War of Independence finally began in 1895, it was launched in part with money rolled into cigars in Tampa. Martí died in battle that same year, but the war he started succeeded. Cuba became independent in 1898. Tampa's cigar workers had helped make it happen.

"I want the first law of our republic to be the tribute of Cubans to the full dignity of man... With all, and for the good of all."

— José Martí, Speech at Liceo Cubano, Ybor City, 1891

The Threat

The factory owners were not stupid. They understood what was happening on their floors. The lectores were turning their workers into radicals — union organizers, strike leaders, anarchists, socialists. The same workers who donated to Cuban independence were also demanding better wages, shorter hours, and the right to organize. The same platform that broadcast Victor Hugo also broadcast calls for general strikes.

Throughout the early 1900s, Ybor City was rocked by labor unrest. Major strikes hit in 1899, 1901, 1910, and 1920. Workers walked out by the thousands. Factories closed for months. The owners blamed the lectores. "These readers," one manufacturer complained, "fill the heads of the workers with ideas that make them dissatisfied with their lot."

The manufacturers tried various tactics. Some banned "inflammatory" material. Others tried to hire their own lectores who would read only approved content. The workers refused. They had hired the lectores. They would decide what was read. In one famous incident, workers at a factory walked out en masse when the owner tried to censor the reading material. They didn't come back until the owner relented.

The standoff continued for decades. The lectores kept reading. The workers kept striking. The owners kept losing money. Something had to give.

The End

The lectores didn't die all at once. They were killed slowly, by technology and economics and the determined opposition of capital.

Radio arrived in the 1920s. Suddenly, factory owners had an alternative: install radios, play music and entertainment, drown out the lectores with noise that didn't include revolutionary manifestos. Workers were divided. Some preferred the lectores. Others liked the music. The unified front began to crack.

The Great Depression delivered the final blow. By 1931, the cigar industry was collapsing. Factories were closing. Workers who still had jobs couldn't afford to pay lector salaries. And the manufacturers — who had waited decades for this moment — moved to ban the practice entirely. One by one, the tribunes came down. The last lector in Tampa was fired in 1931.

The timing was not accidental. The owners had learned that a major strike was being planned. They banned the lectores specifically to prevent workers from organizing. Without the platform, without the shared information, without the daily education in labor history and radical politics, the workers were isolated. The strike never happened.

"When the lectores were removed, something died in the cigar factories. The workers became just workers. Before, they had been citizens of a republic of ideas."

— Ybor City historian, Oral history interview, 1980s

The Legacy

The profession of lector is extinct. No one reads aloud in factories anymore. The wooden tribunes are gone. The tradition survives only in museums and memory.

But what the lectores created didn't entirely disappear. The cigar workers of Ybor City — many of them immigrants who arrived illiterate — became some of the most educated working-class people in America. They built mutual aid societies, founded labor unions, started newspapers. Their children went to college. Their grandchildren became doctors, lawyers, professors. The knowledge that flowed through those factories for fifty years changed families for generations.

There's also the matter of Cuba. The revolution that José Martí launched from Tampa's cigar factories succeeded. The money that workers rolled into their cigars helped buy guns, ships, and supplies. The lectores who read Martí's words aloud turned a political movement into a religion. Tampa earned its nickname: "The Cradle of Cuban Liberty."

Today, you can visit Ybor City and see what remains. The old factory buildings still stand, converted into restaurants and shops. The Ybor City Museum State Park has exhibits about the cigar industry and the lectores. A few small cigar shops still hand-roll tobacco the old way. But no one reads aloud.

The lectores represented something that American capitalism has always found threatening: workers who think. Not workers who listen to whatever management wants them to hear, but workers who control their own education, who choose their own reading, who turn a factory floor into a forum. The platform gave them power. The literature gave them language. The newspapers gave them context. For fifty years, the cigar workers of Tampa were the most informed laborers in the country.

The manufacturers understood this, which is why they spent decades trying to silence the lectores. When they finally succeeded, they didn't just end a tradition. They ended an experiment in worker education that has never been replicated. The tribunes are gone. The voices are silent. What remains is a question: What would American labor look like if every factory had a lector?

We'll never know. The last one was fired in 1931, and nobody reads to the workers anymore.

Visiting Ybor City

The Ybor City Museum State Park (1818 E. 9th Avenue) offers exhibits on the cigar industry and the lectores. Several small cigar shops still operate in the historic district, including J.C. Newman Cigar Company — the last operating cigar factory in Tampa. The neighborhood retains its historic architecture and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.