Every January, several hundred thousand people gather along Bayshore Boulevard in Tampa to watch a 137-foot steel barge, dressed up as an 18th-century pirate ship, get towed into the harbor by tugboats. The ship carries over 750 men in pirate costumes, firing cannons and throwing beads at the crowds, reenacting the "invasion" of Tampa by the legendary buccaneer Jose Gaspar. It is, by most accounts, the third-largest parade in America, trailing only the Rose Parade and Macy's Thanksgiving spectacular. It generates over $40 million in local economic activity. And it celebrates a man who never existed.

This is not disputed. Even the Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla, the private social club that has organized the festival since 1904, has conceded the point. Their own centennial history document, published in 2004, notes that "scholarly research conducted in both Spanish and American archives has not uncovered any evidence of Gaspar's existence." They add, with the cheerful indifference of people who have built an entire civic identity around a hoax: "Whether Gasparilla, the pirate, actually existed or not is a moot point."

"Whether Gasparilla, the pirate, actually existed or not is a moot point."

— Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla, Centennial History Document, 2004

But how does a city invent a pirate? How does a fiction become so embedded that the Library of Congress once catalogued it as fact, that a major NFL franchise named itself for the myth, that an entire regional economy organizes itself around celebrating someone's fabricated biography? The story of Jose Gaspar is really a story about American boosterism, about the malleability of history when money is involved, and about how desperately we want our places to have romantic pasts even when they don't.

The Legend, Such As It Is

According to the story that Tampa has told itself for over a century, Jose Gaspar was born to a Spanish aristocratic family around 1756. He entered the Naval Academy in Barcelona at eighteen, rose to Lieutenant by twenty-two, and served honorably until some combination of romantic betrayal, false accusations, and disillusionment with the crown drove him to piracy. The details vary depending on who's telling it. In one version, he was a councilor to King Charles III who was framed for stealing the crown jewels by a spurned lover. In another, he was a troubled youth who kidnapped a girl for ransom and was given a choice between prison and the Navy. The inconsistencies never seem to bother anyone.

What the legends agree on is that Gaspar established a "pirate kingdom" on Gasparilla Island, terrorizing ships along Florida's Gulf Coast for nearly forty years. Male prisoners were killed or forced to join his crew. Female captives were taken to Captiva Island - supposedly named for this very practice - to be held for ransom or as concubines. His treasure allegedly amounted to $30 million, a figure that would have represented nearly four times the entire U.S. military budget in 1821. The man's haul would have made him, adjusted for inflation, one of the wealthiest pirates in history.

The most elaborate subplot involves a Spanish princess named Josefa de Mayorga, daughter of a Viceroy, whom Gaspar captured in 1801. Smitten, he tried to win her love by showering her with treasures. When she repeatedly rejected him, his crew grew restless and pressured him to dispose of her. In a moment of anguished madness, Gaspar beheaded the princess himself, then remained inconsolable for the rest of his days. He buried her on a nearby island and named it "Useppa" in her honor. It's all wonderfully operatic. It's also complete nonsense.

The Evidence (There Isn't Any)

The case against Gaspar's existence isn't merely that we lack evidence for him. It's that we have actively searched for such evidence and found nothing - while finding considerable evidence that the entire story was invented in the early twentieth century for commercial purposes.

No mention of Jose Gaspar appears in Spanish or American ship logs, court records, newspapers, or archives from his supposed era. No ruins, artifacts, treasure, or murder victims attributed to Gaspar have ever been discovered. The USS Enterprise, which supposedly destroyed Gaspar's fleet in 1821, was documented in Cuba at the time, not Florida. Captain Lawrence Kearney's ship was in New York Harbor for repairs in early 1821 and spent the rest of that year patrolling off Cuba's southwest coast. The heroic final battle simply could not have happened.

Even more damning: the place names supposedly given by Gaspar - including "Gasparilla," "Captiva," and "Sanibel" - appear on Spanish and English maps from the early 1700s, decades before the pirate supposedly arrived. A Bernard Romans map from 1774 shows "Boca Gasparilla" - twelve years before Gaspar allegedly began his reign of terror. Historical documents suggest the name actually came from Friar Gaspar, a Spanish missionary who visited the native Calusa people in the 1600s. The suffix "-illa" means "beloved" in Spanish, not "outlaw" as some legend-promoters have claimed.

"The heroic final battle simply could not have happened. The USS Enterprise was documented in Cuba at the time, not Florida."

The timing is also wrong. Large-scale piracy was rare in the Gulf of Mexico during the late 1700s and early 1800s. This was well after the "Golden Age of Piracy" (roughly 1650-1725), and every major pirate of that era had been killed by 1730. A lone buccaneer operating for forty years in the early nineteenth century, accumulating treasure worth four times the U.S. military budget, would have been the most remarkable pirate in history - and somehow escaped all contemporary notice.

The Con Man and the Railroad

So where did Gaspar come from? The trail leads to a fisherman, a railroad, and a publicist who cheerfully admitted he made the whole thing up.

The original source appears to be Juan Gomez, known as "Panther Key John," a fisherman, hunting guide, and occasional blockade runner who lived on Panther Key in Florida's Ten Thousand Islands. Gomez claimed at various times to have been born in 1776, 1778, 1781, or 1795, in Honduras, Portugal, Corsica, or Mauritius. Shortly before drowning in 1900, he claimed to be 122 or 123 years old. He told tourists he had been Gaspar's "cabin boy" and "brother-in-law," and was known to sell fake treasure maps to gullible visitors. Most historians believe he simply invented entertaining stories for tourists and profit.

The legend might have died with Gomez if not for the Charlotte Harbor and Northern Railway. Around 1905-1907, a publicist named G.P. "Pat" LeMoyne wrote a promotional brochure for the railroad, combining and embellishing Gomez's tall tales. The brochure was designed to promote the Gasparilla Inn in Boca Grande and increase the value of land holdings along the rail line. LeMoyne gave the pirate a dramatic biography, complete with the beheaded princess and the glorious final battle.

Here's the remarkable part: in 1949, a retired Pat LeMoyne gave a lecture where he admitted his biography of Jose Gaspar was a fabrication written in a dramatic style "tourists like to hear." By then, of course, it was too late. The legend had taken hold, and Tampa had built an entire festival around it.

How Tampa Got a Pirate

In 1904, Louise Francis Dodge (society editor of the Tampa Tribune) and George W. Hardee (a New Orleans-born engineer working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) wanted to enliven Tampa's May Day celebration. Hardee, familiar with Mardi Gras traditions, suggested a krewe-style event with participants dressed as pirates. They borrowed the obscure Gasparilla story from a hundred miles down the coast and gave the pirate his first name "Jose" and death date of 1821.

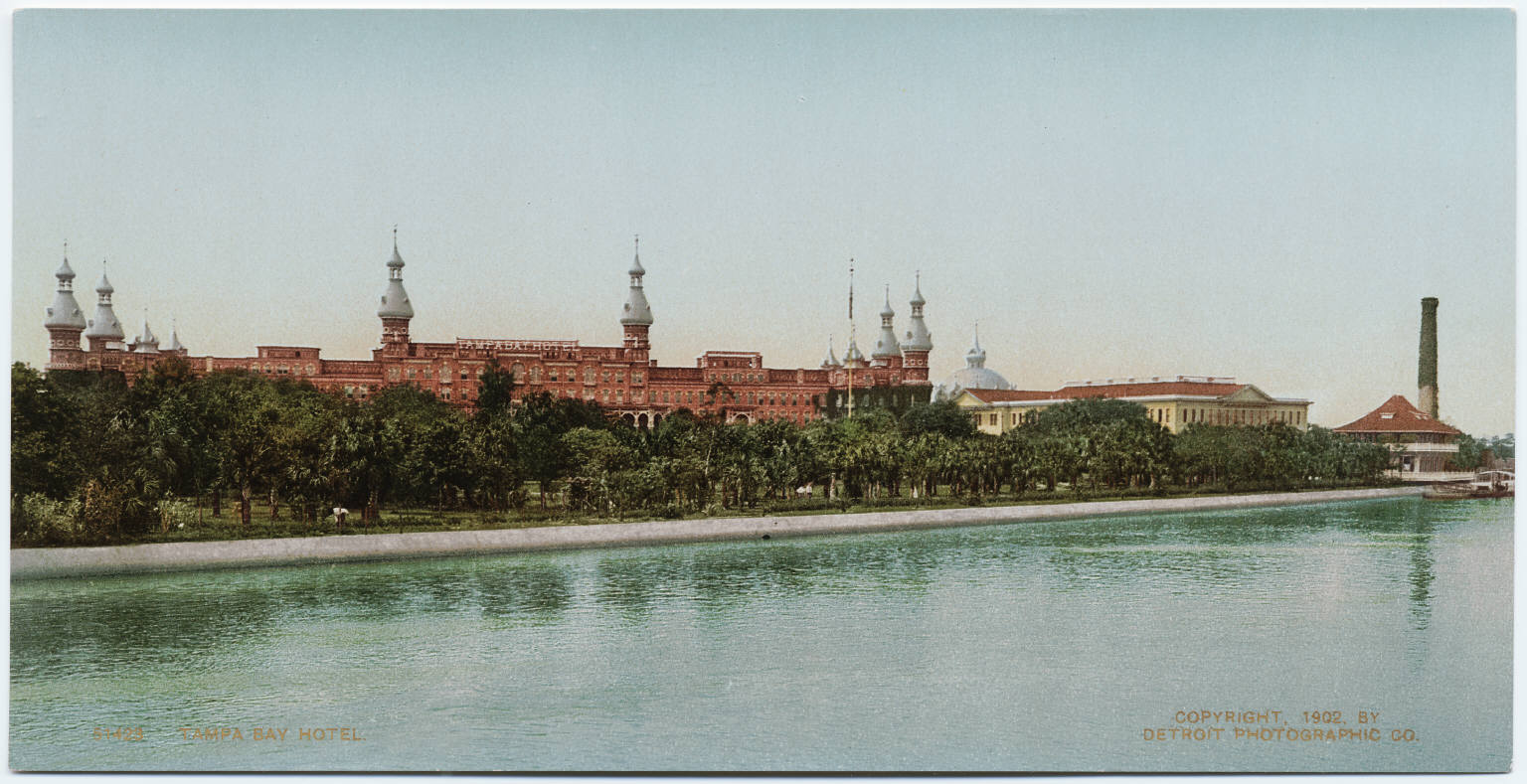

On May 4, 1904, about fifty Tampa businessmen, with costumes rented from New Orleans, rode into Tampa on horseback and "captured the city" during the May Day Festival Parade. The public had been told a pirate ship called the "Octopus" was anchored offshore, but anyone attempting to see it was "threatened with death." A coronation ball was held two days later at the Tampa Bay Hotel, Henry Plant's Moorish palace that still stands today. The surprise invasion delighted the city, and a tradition was born.

The festival grew. In 1911, they started using an actual ship (a borrowed three-masted schooner). By 1937, the Ye Mystic Krewe purchased its own vessel. In 1954, they commissioned the Jose Gasparilla II - described as the world's only fully-rigged pirate ship built for "piratical purposes" in 200 years. It cost $100,000 and took seven months to build. It's actually a 137-foot steel barge converted to look like a West Indiaman, and it cannot propel itself - it must be towed by tugboats. A separate crew of sober operators actually controls the ship while the pirates party.

The Pirates Who Rule Tampa

The Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla was not simply a party-planning committee. For most of its history, it was an invitation-only social organization drawn from Tampa's business and civic elite - white, male, and exclusive. Membership overlapped with the Tampa Chamber of Commerce, the Palma Ceia Country Club, and the Tampa Yacht Club. An invitation to join the krewe was a sign that you had "arrived in the community."

As one historian noted: "Certainly as Tampa was growing in the 1950s and '60s, there was a great desire among new businessmen in the area, particularly people who were new to the area, to become a part of either Ye Mystic Krewe or join Palma Ceia Country Club or Tampa Yacht Club, so you can become established in society, but also in business circles."

The festival served dual purposes: city promotion and exclusive social networking. The coronation balls, debutante presentations, and annual invasions were performances of status, rituals through which Tampa's power structure displayed and reproduced itself. All historical evidence shows the legend was "essentially the product and property of Tampa's Anglo establishment."

This created an obvious problem in a city with significant Latin and Black populations. Despite Tampa being home to one of the largest Hispanic communities in the American South in the early twentieth century - Ybor City's cigar workers were Cuban, Italian, and Spanish - the krewe remained exclusively white. Black residents and Latino businessmen were excluded from the network of power that the festival represented.

The Super Bowl Integration Crisis

The exclusionary policies finally made national news in 1991, when Tampa was set to host Super Bowl XXV. By the 1980s, local minority organizations had begun pointing out that exclusion from YMKG symbolized continued exclusion from Tampa's top social and economic circles. When the NFL learned of the parade's policies, civil rights leaders saw an opportunity to force change on a national stage.

Mayor Sandy Freedman threatened to pull city services - police security, permits, everything. The krewe was faced with a choice: integrate or cancel. They claimed it was "too late" to expand membership for that year's parade and chose to cancel the entire event. The city scrambled to create "Bamboleo," a hastily organized multicultural replacement festival. It rained. The festival bombed.

In a tragicomic footnote, the Ku Klux Klan attempted to register for the Bamboleo parade but missed the deadline. Tampa's attempt to create an inclusive replacement for its exclusive pirate festival was nearly crashed by white supremacists.

Later in 1991, the krewe quietly admitted two Black members and agreed to allow additional krewes to participate. The parade returned in 1992 with an expanded, more diverse participant list. The all-Black Buffalo Soldiers krewe joined that year. Today there are Latin krewes, female krewes, a gay krewe, and even a krewe of chefs. The transformation was real, even if it took the threat of national embarrassment to force it.

"The krewe claimed it was "too late" to expand membership and chose to cancel the entire event rather than integrate."

The Legend Machine

What's remarkable about the Gaspar story is how it achieved legitimacy through repetition and institutional support. In 1923, a Boston historian named Francis B.C. Bradlee received a copy of the Gasparilla Inn brochure and, without fact-checking, included the fictional pirate in his book "Piracy In The West Indies And Its Suppression." This accidental inclusion in an otherwise scholarly work has caused ongoing confusion about Gaspar's historical authenticity. Even the Library of Congress was fooled at one point, referring to the Gasparilla documentation as genuine.

In 1936, Edwin D. Lambright, a Tampa Tribune writer and krewe member, wrote the "definitive" history of Jose Gaspar, treating him as a real person. The book solidified the legend's details and gave future generations a authoritative-sounding source to cite. Each retelling added credibility. Each repetition made the fiction more real.

The legend even shaped Tampa's professional sports identity. When Tampa was awarded an NFL franchise in 1976, the team name was chosen through a public contest inspired by Gasparilla tradition. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers' logo was designed by Lamar Sparkman, a Tampa Tribune cartoonist and krewe member. Raymond James Stadium features a 103-foot, 43-ton pirate ship replica that fires cannons when the team scores - fans call it a "Mini Gasparilla." The fake pirate has become so embedded in Tampa's identity that distinguishing fiction from reality seems almost beside the point.

What the Fake Pirate Tells Us

There's something both charming and unsettling about Tampa's commitment to its invented buccaneer. On one hand, it's just a party - a really good party that generates $40 million annually and brings people together. Gaspar harms no one. The costumes are fun. The beads are free. Who cares if the pirate was real?

On the other hand, the Gasparilla story is a case study in how history gets made and who gets to make it. The legend was created by railroad promoters to sell land. It was adopted by Tampa's white business elite and turned into a vehicle for social exclusion. It was defended so fiercely that an entire festival was cancelled rather than share it. The "tradition" that Tampa celebrates is barely a century old, invented by advertisers and maintained by those who profit from it.

Perhaps the most honest moment in Gasparilla history came from Pat LeMoyne himself, the publicist who admitted in 1949 that he'd written "a cockeyed lie without a true fact in it." He understood what he was doing. He wrote in a dramatic style "tourists like to hear." He gave people what they wanted: a romantic past for a scrappy city that didn't have one.

Tampa took that lie and ran with it. They built a ship (that can't sail). They created a krewe (that excluded most of the city). They made a fake pirate real through sheer force of repetition and commercial will. And every January, hundreds of thousands of people gather to celebrate a man who never existed, because at some point the fiction became more important than the truth.

That's the most American story of all.

When to See It

Gasparilla Pirate Fest takes place annually in late January. The invasion and parade draw roughly 300,000 spectators. Plan ahead - hotels book up months in advance, and traffic along Bayshore Boulevard is apocalyptic.