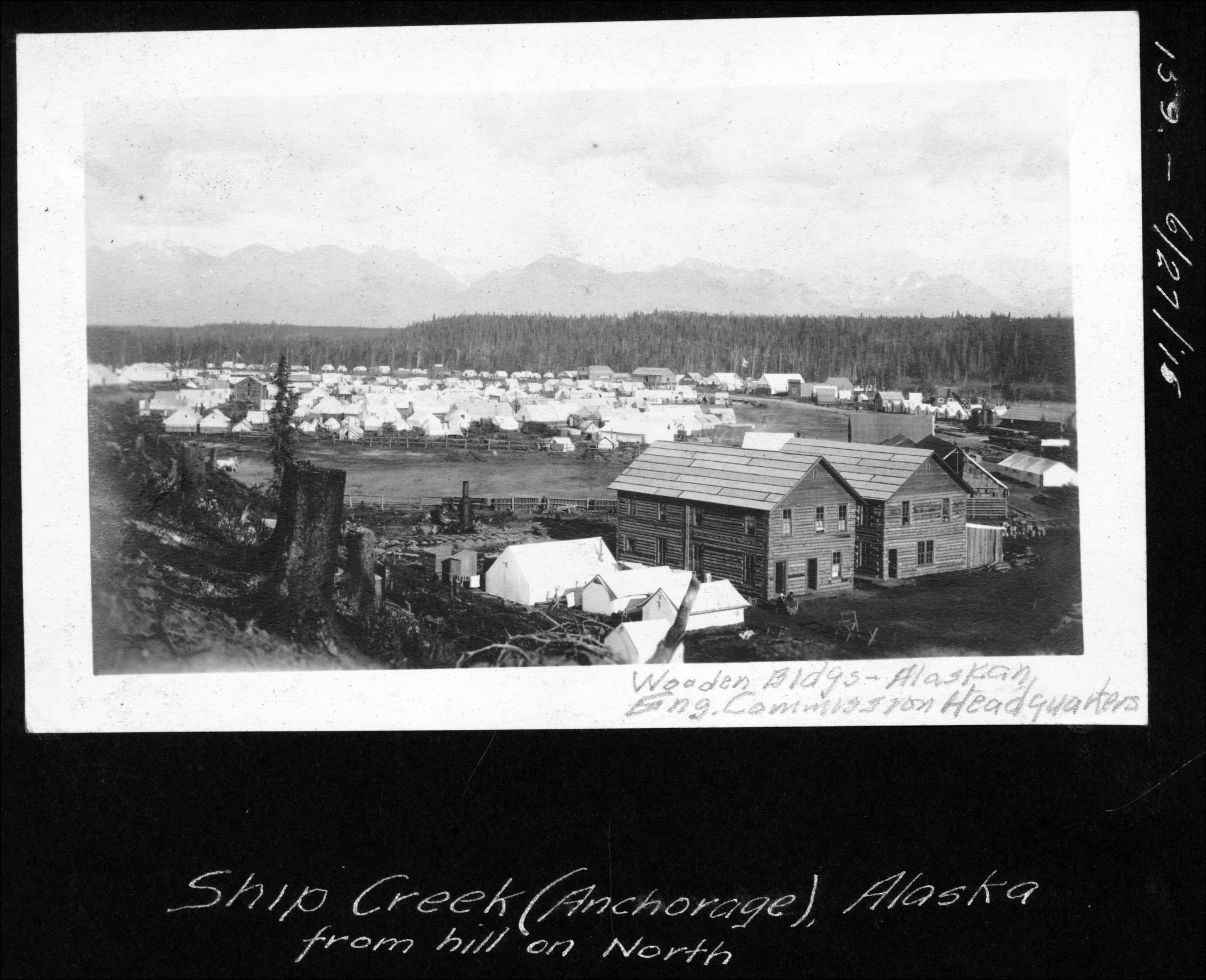

Anchorage tells a founding story about itself. In 1914, Congress authorized the Alaska Railroad. In 1915, workers arrived at Ship Creek to build a construction camp. A tent city sprang up. Lots were auctioned. A town was born. It's a classic American origin story: empty wilderness, hardy pioneers, civilization carved from nothing.

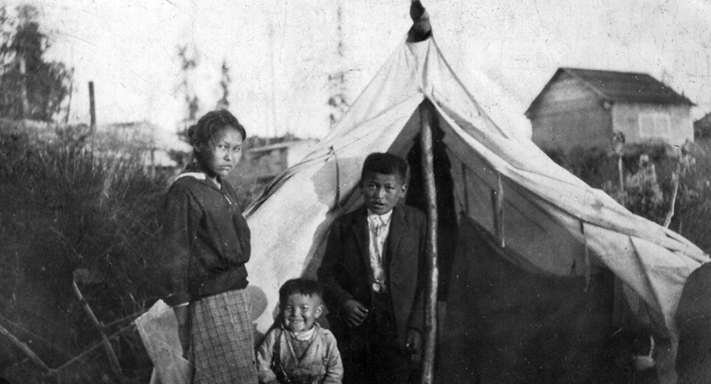

The story is a lie. The land wasn't empty. The Dena'ina Athabascan people had lived in the Cook Inlet region for centuries — fishing the salmon runs, hunting in the mountains, maintaining a complex network of villages and trade routes. When the railroad workers arrived, they were building on Dena'ina land. Everyone knew it. Nobody cared.

Then, in 1918, the Spanish flu came to Alaska. What happened next is the founding tragedy that Anchorage has never acknowledged: the near-extinction of the Dena'ina, the abandonment of eight villages, the demographic collapse that conveniently cleared the way for colonial development. Anchorage wasn't built on empty land. It was built on graves.

The People Who Were There

The Dena'ina — whose name means "the people" — had occupied the Cook Inlet basin for at least a thousand years before Europeans arrived. They were the only Athabascan group to live on saltwater, adapting their inland hunting culture to the resources of the coast. They fished for salmon, hunted beluga whales, and traveled seasonal rounds between fishing camps, hunting grounds, and winter villages.

By the early 1900s, despite a century of contact with Russian traders, American prospectors, and Christian missionaries, the Dena'ina still maintained their presence. Eight major villages dotted the Cook Inlet region: Eklutna, Knik, Tyonek, Susitna Station, Kalifornsky, Point Possession, Nikiski, and others. The total population was probably around 1,500 people — diminished from pre-contact levels, but still a living culture.

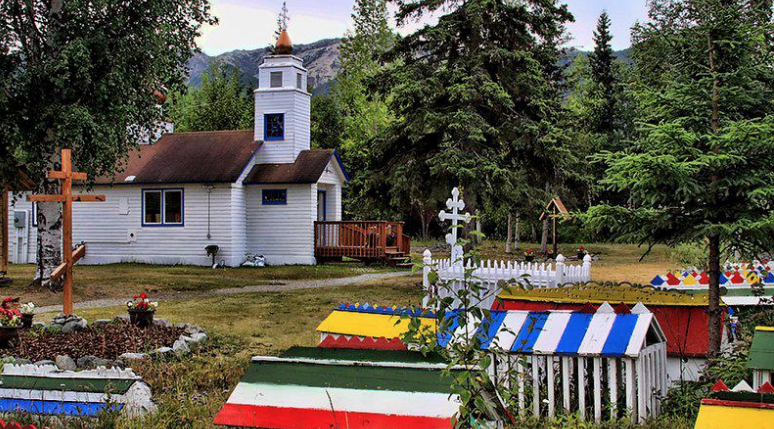

The villages had adapted. Russian Orthodox missionaries had converted many Dena'ina in the 1840s, creating a syncretic culture that blended Christianity with traditional practices. The distinctive spirit houses at Eklutna Cemetery — brightly painted wooden structures placed over graves — represented this fusion. The Dena'ina were changing, but they were surviving.

"We had been here forever. The rivers, the mountains, the inlet — these were our places. We had names for everything. Then the sickness came, and suddenly there was almost no one left to remember the names."

— Dena'ina elder, Oral history, 1970s

The Railroad Arrives

In 1914, Congress passed the Alaska Railroad Act, authorizing construction of a railroad from Seward to Fairbanks. The project would require thousands of workers, a construction headquarters, and a supply depot. Federal surveyors chose Ship Creek, on the northern shore of Cook Inlet, as the site for the main construction camp.

Ship Creek was Dena'ina territory. The creek itself was called Dgheyay Kaq' in Dena'ina — a fishing site used for generations. But the railroad needed the location, and nobody asked the Dena'ina's permission. Workers began arriving in 1915. Within months, a tent city of 2,000 people had sprung up at the creek's mouth.

The town that became Anchorage was formally established on July 10, 1915, when the federal government auctioned 655 lots to eager buyers. The winning bids totaled over $148,000 — a fortune in 1915 dollars, for land that had belonged to the Dena'ina since before memory. The auction was legal under American law. It was also theft.

The railroad brought more than workers. It brought disease vectors — thousands of men from the Lower 48, crowded into camps with poor sanitation, carrying pathogens that Alaskan Indigenous peoples had never encountered. For three years, the Dena'ina watched the tent city grow. Then the flu arrived.

The Pandemic

The Spanish flu reached Alaska in the fall of 1918, arriving on ships from Seattle. It spread along the coastlines and up the rivers, following the routes that connected Alaska's scattered settlements. By October, it had reached Anchorage.

Anchorage's white residents suffered, but most survived. The town had doctors, a hospital (of sorts), and access to supplies. Officials downplayed the severity at first — the Anchorage Daily Times ran headlines minimizing the danger — but eventually quarantines were imposed and the outbreak contained. Among the approximately 1,900 white residents of Anchorage, eight people died.

The Dena'ina had no such luck. They had no immunity to influenza, no access to medical care, no government officials downplaying their danger and then rushing to help. When the flu hit the villages, it burned through the population like wildfire.

The death toll was catastrophic. Approximately 50% of the Dena'ina population in the Cook Inlet region died during the 1918-1919 pandemic. Entire families were wiped out. In some villages, there weren't enough healthy people left to bury the dead. Bodies lay in houses for weeks because no one remained to move them.

The Numbers

Alaska Natives suffered 82% of all flu deaths in the territory during 1918-1919, despite being a fraction of the population. The per capita death rate among Alaska Natives was higher than anywhere else in the world except Samoa. Between 1918 and 1919, an estimated 51% of all deaths in Alaska Territory were from influenza.

The Abandoned Villages

In the aftermath of the pandemic, eight Dena'ina villages were completely abandoned. Kalifornsky, Point Possession, Nikiski, Anchor Point, and others simply ceased to exist. The survivors, too few to maintain their communities, relocated to the remaining villages or dispersed entirely.

The village of Knik, once a major Dena'ina settlement and trading post, was devastated. Susitna Station was abandoned. Throughout the region, the network of communities that had sustained Dena'ina culture for centuries collapsed. What had been a living society became a remnant.

Only Eklutna survived as a functioning Dena'ina village — and barely. Located about 25 miles north of Anchorage, Eklutna had been occupied for over 800 years. It was the oldest continuously inhabited site in the region. After the pandemic, it became essentially the last.

The timing was grimly convenient for colonial development. The railroad needed land. The flu cleared the land. The villages that might have complicated expansion simply disappeared. The Dena'ina who might have resisted were dead or scattered. Anchorage grew without opposition.

"Six hundred of seven hundred Dena'ina... were "wiped out". We're only a few people left."

— Shem Pete, Dena'ina elder and historian

The Erasure

Anchorage's official history rarely mentions the Dena'ina, and almost never mentions the pandemic. The standard narrative jumps from "wilderness" to "railroad town" as if the land had been waiting empty for American development. The collapse of Indigenous society that enabled that development goes unacknowledged.

This erasure is physical as well as historical. Dena'ina place names were replaced with English ones. Dgheyay Kaq' became Ship Creek. Traditional sites were paved over, built upon, transformed beyond recognition. The landscape itself was rewritten to erase Indigenous presence.

Today, Alaska Natives comprise only about 10% of Anchorage's population, compared to nearly 20% statewide. The Dena'ina — whose ancestors lived here for a millennium — are a tiny minority in a city built on their land. Most Anchorage residents have never heard of them. The founding tragedy remains buried.

The Indigenous Place Names Project

Efforts are underway to reclaim Dena'ina presence in Anchorage's landscape. The Indigenous Place Names Project, led by historian Aaron Leggett, documents traditional Dena'ina names for locations throughout the region. But most Anchorage residents remain unaware of the history beneath their city.

What Remains

Eklutna survives. The village, now home to about 70 residents, maintains the Eklutna Historical Park, where the famous spirit houses still stand over Dena'ina graves. The cemetery has been in continuous use since approximately 1650, predating Russian contact. It is the most visible reminder of Dena'ina presence in the Anchorage area.

The Dena'ina language survives, barely. Fewer than 100 fluent speakers remain. Efforts to revitalize the language are underway, but the knowledge lost in the pandemic — the elders who died, the stories never passed down, the children never taught — can never be fully recovered.

The Eklutna tribe and other Dena'ina organizations continue to advocate for recognition, for land rights, for acknowledgment of what was lost. But Anchorage has never formally reckoned with its founding tragedy. There is no memorial to the pandemic dead. No official acknowledgment that the city was built on the ruins of a society it helped destroy.

Visiting Eklutna

Eklutna Historical Park, located 25 miles north of Anchorage off the Glenn Highway, preserves the historic cemetery with its distinctive spirit houses. The park offers guided tours explaining Dena'ina history and the Russian Orthodox influence. The Anchorage Museum also has exhibits on Dena'ina culture and the Indigenous history of the region.